SAUNDERS: Nitrogen gas execution works. Now what does Washington do?

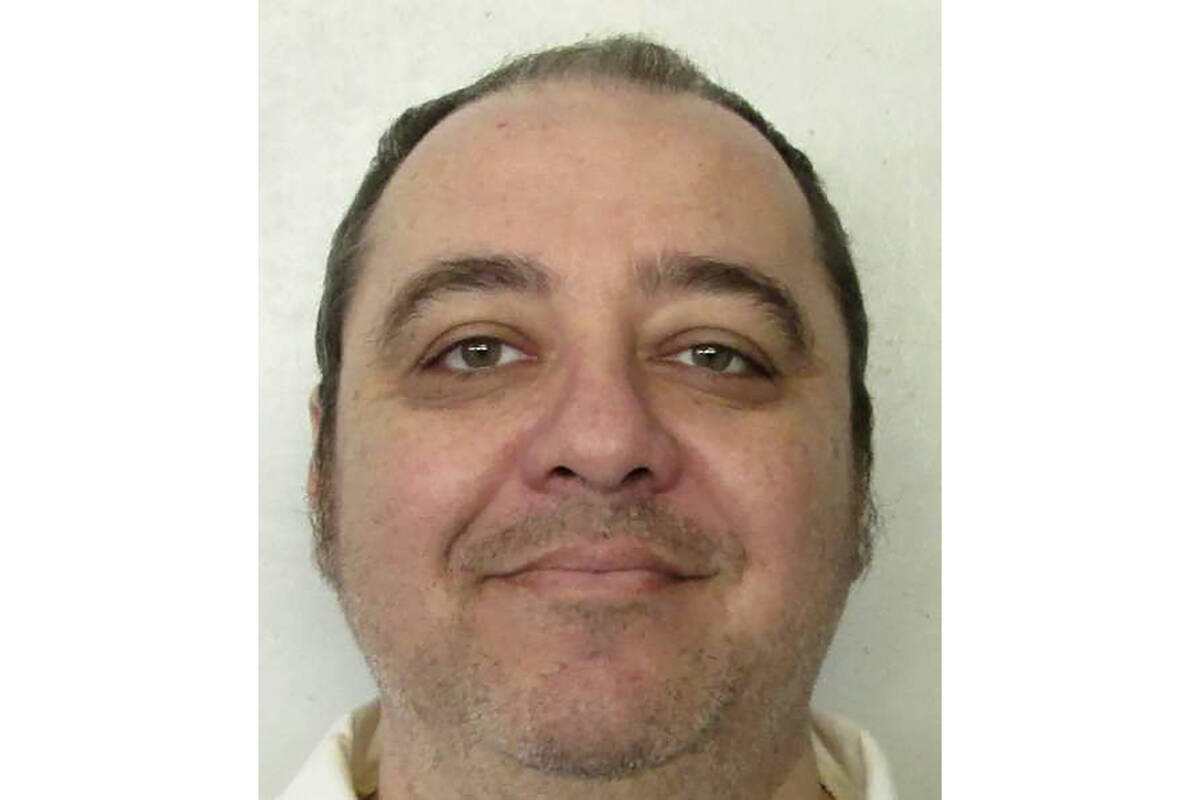

WASHINGTON — Headlines referred to Thursday’s execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith in Alabama by nitrogen hypoxia as “experimental.” A United Nations official warned the method “could amount to torture under international treaties.”

White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre told reporters Friday the White House found the the use of nitrogen gas “very troubling.” She added that President Joe Biden has “broad concern about the death penalty.” Whatever that means.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, one of three justices who wanted to intervene against the execution, opined, “Alabama has selected (Smith) as its ‘guinea pig’ to test a method of execution never attempted before.”

The Washington Post reported on concerned parties who feared Smith might choke and vomit during his execution.

The beltway has shown less interest in Elizabeth Sennett, who in 1988 was found dead in her Colbert County home, after she was stabbed eight times in the chest and once on each side of her neck, according to documents.

Smith ultimately confessed his role in the brutal paid-for-hire murder, al.com reported, as did his accomplice, John Forrest Parker.

Like Smith, Parker was convicted for the murders. Unlike Smith, Parker was executed in 2010.

Sennett’s husband, Charles, a Church of Christ pastor, had agreed to pay Smith and Parker $1,000 each to kill his wife so the widower could collect on her life insurance. After he confessed to police, Charles Sennett killed himself.

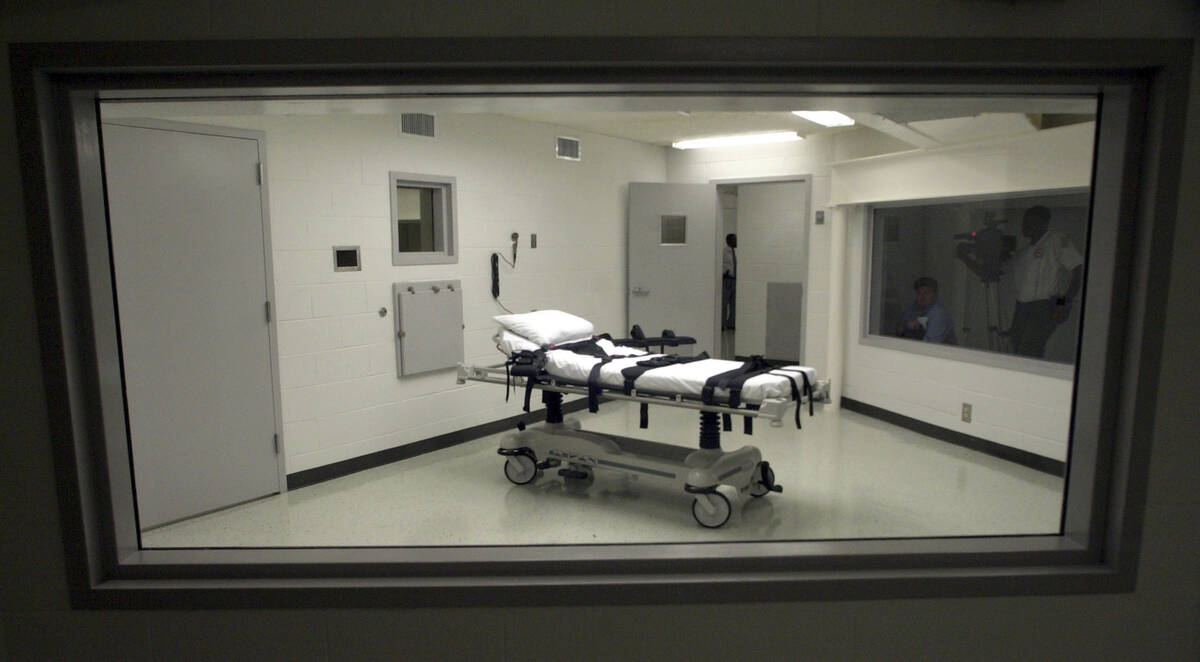

Forget Elizabeth Sennett and how she suffered. Witnesses said that Smith shook and writhed for at least two minutes and breathed heavily after the gas was released into a mask.

Michael Rushford of the tough-on-crime Criminal Justice Legal Foundation wondered if the problem was the mask, or if Smith held his breath, which would prolong the procedure.

CJLF has been advocating for nitrogen-gas execution for years because it’s painless, it doesn’t require needles, and it doesn’t require medical personnel, who can be threatened with losing their licenses. And nitrogen gas is readily available. (“You can get it at Home Depot,” Rushford marveled.)

Death penalty opponents successfully pressured pharmaceutical companies to stop manufacturing lethal injection drugs as an indirect means of preventing authorities from carrying out duly-enacted laws and protocols approved by the courts. They couldn’t change the law — the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of lethal injection under a three-drug protocol — but they could intimidate involved parties.

Lethal injection was adopted as a means to prevent unnecessary pain — and mostly it worked that way.

In 2001, I witnessed the lethal injection of Robert Lee Massie on San Quentin’s Death Row. Massie killed a 48-year-old woman in 1965 and was sentenced to death. He was paroled in 1978, after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned death penalty laws. The following year Massie killed a 68-year-old man during a robbery.

If anything, it was a low-drama event, as Massie had stopped his lawyers from contesting his execution. I did not see evidence of pain.

One last thing: Smith repeatedly filed appeals demanding nitrogen gas in lieu of lethal injection. In denying that legal maneuver, U.S. District Judge R. Austin Huffaker Jr. observed, “It is not lost on the court that Smith vehemently argued for execution by nitrogen hypoxia in his previous litigation only several months ago when he was scheduled for execution by lethal injection.” But really, hypocrisy was the least of Smith’s sins.

Contact Review-Journal Washington columnist Debra J. Saunders at dsaunders@reviewjournal.com. Follow @DebraJSaunders on Twitter.