STEVE SEBELIUS: Public records are for everyone, not just the press

Back when I was a police reporter for the Las Vegas Sun, one of my duties was pulling criminal history reports.

To do that, I’d go to the plaza desk at the Metropolitan Police Department in the old Las Vegas City Hall.

One day, a surly clerk informed me, “If it were up to us, we wouldn’t give you anything.”

Of course you wouldn’t. And that’s one of the reasons it’s not up to the government to decide what information the public, and the press, can have.

Today marks the beginning of Sunshine Week 2022, a week dedicated to open government, open meetings and open records. In Nevada, things could definitely be better.

There are more than 400 exceptions to the state’s public records law, which says all public books and documents should be open to public inspection. Some make sense — you don’t want scammers scraping public records to steal identities — but many others don’t.

Reading the law, you’d think it would be simple to get public records, but that’s often not the way it is.

In many cases, public agencies will demand exorbitant fees simply for searching for records. That may not be a problem for a news organization such as the Review-Journal, but what impact does that have on a regular person who wants to get a record that should be available and free?

Public agencies try to justify the fees by saying it takes staff time to gather them and then, in some cases, a legal review is necessary. But the law clearly says fees must not exceed the “actual cost” of providing records, and a law that allowed for charging extraordinary fees for larger requests was repealed in 2019.

Leave aside the crushing irony of a taxpayer-funded agency telling a taxpayer that taxpayer-paid employees working in a taxpayer-funded building need to charge taxpayers to access a taxpayer-owned record in a taxpayer-financed computer system.

The law also says public agencies have five days to either provide a record or tell the person who requested it that it will take more time. They then must give an estimate of when those records will be available. Requests routinely drag out beyond that deadline.

And lawsuits to obtain records — again, something a newspaper or television station can afford, but a regular person probably cannot — are common. The Review-Journal’s lawyers routinely win fees after public records fights, but those fights take time.

And that’s when the records are even available. In one egregious recent case, Las Vegas officials destroyed a video recording of an alleged fistfight between two councilwomen that took place at City Hall despite the fact that those officials knew the Review-Journal was seeking the video. That kind of contempt for the public should carry a criminal penalty.

And why would public officials drag their feet, conceal or even destroy records? The oldest excuse there is: to save face. They know public access to public information may reveal some things that they just don’t want the public to know.

It’s not just journalists who suffer in that instance, although most of us do wake up and wonder, as Bob Woodward of The Washington Post once so memorably put it, “What are the bastards hiding?” It’s also the public.

What happens when a regular person, angry about a neighborhood project or constant road construction, goes down to City Hall to demand to see emails between officials and contractors? When a clerk tells that citizen, “That’s going to cost you $5,000 just for us to collect those records. We’ll need half up front, please?”

That frustrated citizen goes away, and a potential scandal is averted.

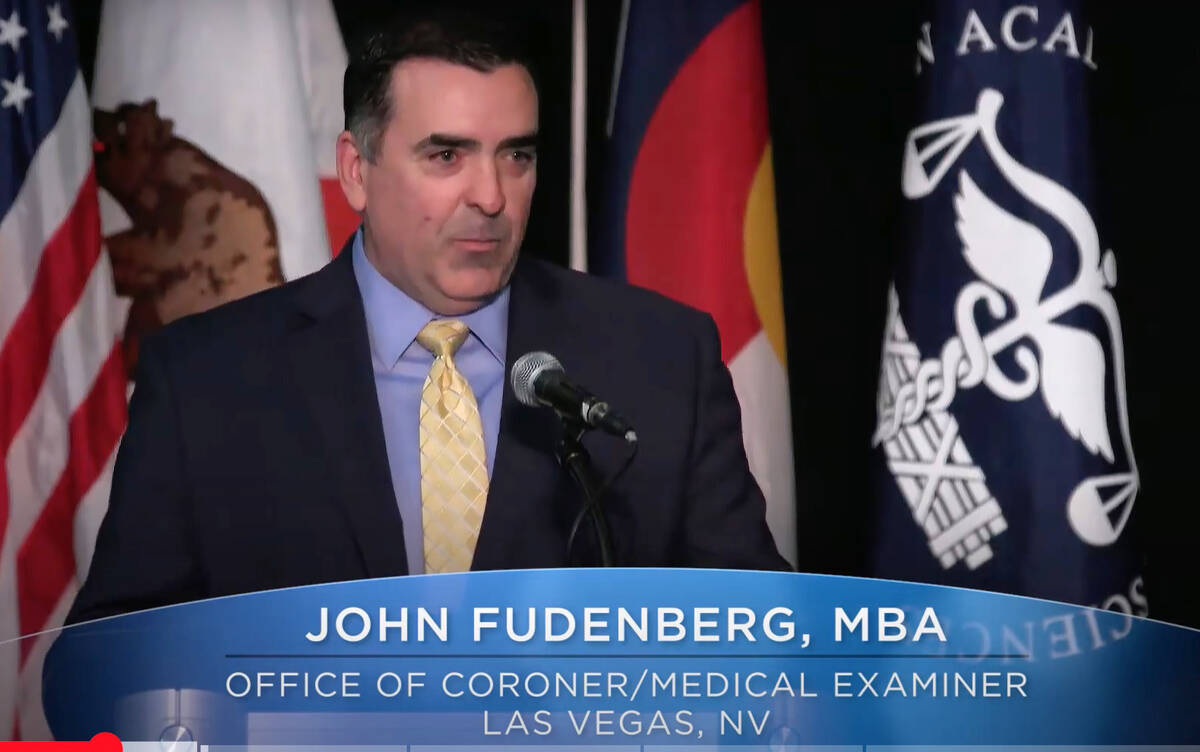

The Legislature has made progress in opening access to records in recent years, although in nearly every session lobbyists for open government must deal with government employees lobbying lawmakers to make it harder to get records. Clark County’s former lobbyist (who was also the coroner) once testified against a public records bill saying news organizations were just trying to sell newspapers.

That particular lobbyist was later found to have exaggerated his credentials and to have made money for personal appearances on government time, a story that was made possible in part by — you guessed it — a careful review of public records.

So on this Sunshine Week 2022, let’s give thanks for the laws that enable anybody — reporter or regular Joe — to demand records that keep our government accountable. But let’s also remember that there’s still a long way to go to find out what the bastards are hiding.

Contact Steve Sebelius at SSebelius@reviewjournal.com. Follow @SteveSebelius on Twitter.