STEVE SEBELIUS: Special sessions? The voters like it like that

Here we go again.

The Legislature convened in special session last week, for the 31st time in state history.

There are two basic kinds of special sessions: those convened by an urgent public crisis and those called at the end of a regular session to complete work unfinished by deadline.

Oh, and the third kind: those called to give away large sums of public dollars to wealthy private corporations or sports teams.

This time, lawmakers gathered to fill the gaping budget hole created by the business shutdown occasioned by the coronavirus pandemic. It’s the worst fiscal downturn ever faced by the state, and it came upon Nevada virtually overnight.

Sudden problems, or even long-festering ones that finally become acute, are among the reasons some give for suggesting that Nevada should finally implement annual sessions of the Legislature, which presently is constitutionally limited to meeting for 120 days every other year.

From statehood in 1864 to 1999, when the 120-day limit went into effect, Nevada got by with just 16 special sessions, an average of one every 8.4 years. But from 1999 to the present, there have been 15 sessions, an average of one every 1.4 years.

Some of those sessions last a single day or just a few hours. Some go much longer. The Great Budget Standoff of 2003 sparked two special sessions, one lasting nine days and another stretching 27 days.

An annual session — even one limited to a couple of months — would relieve the Legislature of the increasingly complicated task of passing a two-year budget premised on the best guess about tax revenues in the next 24 months. But it could also allow the state the opportunity to address challenges that arise in the long 19 months between our current sessions.

Most state legislatures meet annually, in part for that reason. Only Nevada, Montana, North Dakota and Texas have biennial sessions.

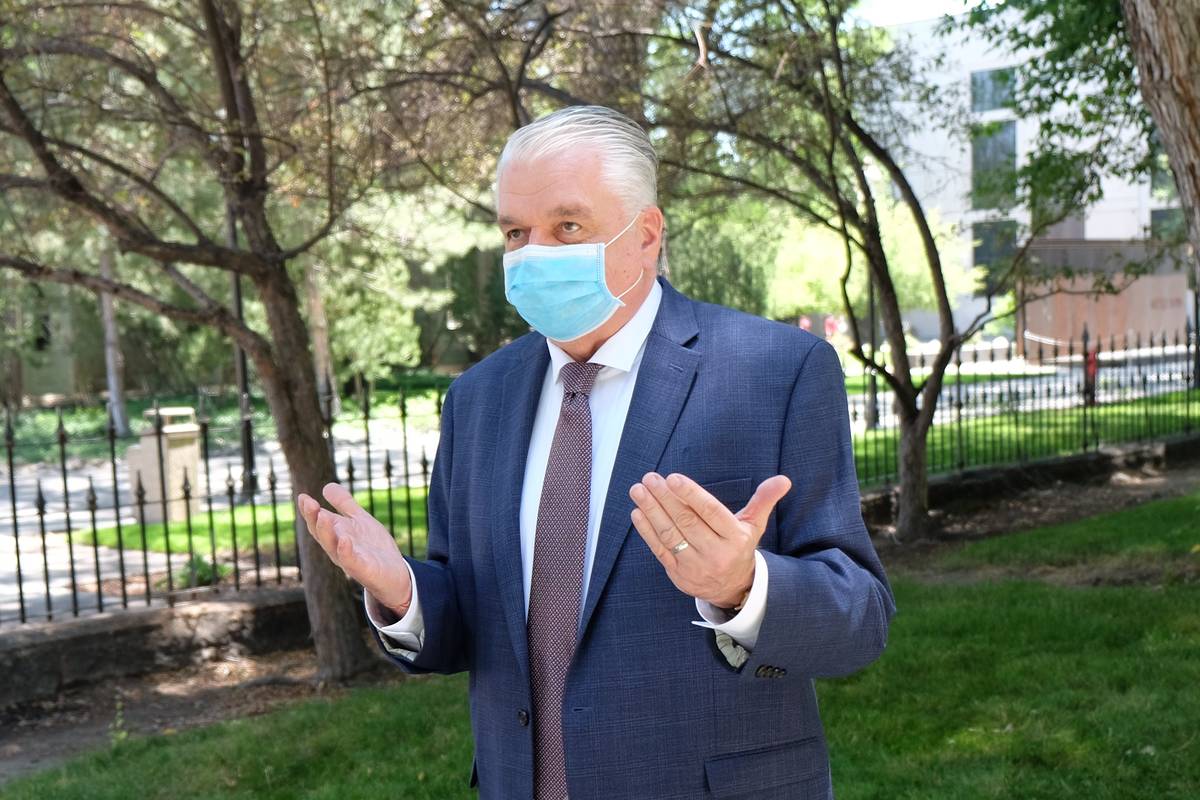

Before this special session took on the budget, there was some partisan constitutional wrangling. As Senate Majority Leader Nicole Cannizzaro, D-Las Vegas, introduced special rules that would allow for remote participation and even voting by COVID-19 quarantined lawmakers, Minority Leader James Settelmeyer, R-Minden, objected.

Under the constitution, Settelmeyer said, the Legislature must meet at the seat of government, Carson City. Remote lawmakers could be anywhere in the world. His counterpart in the Assembly, Robin Titus, R-Wellington, said sick lawmakers in the past were excused from attendance but not allowed to participate or vote.

And yes, the state constitution does specify that meetings of the Legislature must be in Carson City, and yes, the point having been made, any close remote vote could later be called into question.

But there also may be a bit of regionalism baked into that objection, because the Republican caucuses in both the Senate and Assembly have a majority of Northern Nevada members. They certainly don’t want to set a precedent for legislative action taken in another part of the state, lest the people-rich South finally make good on its threats to move the capital to Las Vegas.

That wasn’t the only constitutional debate either. Even as lawmakers pored over spreadsheets and listened to hours of testimony about the impact of cuts, some of them were being sued in Clark County District Court.

The Nevada Policy Research Institute sued nine lawmakers who also happened to work as public employees, on the grounds that under the state constitution’s separation of powers clause, people who work in the executive branch should not also serve in the legislative branch. Named in the lawsuit are Democratic leaders Cannizzaro and Assembly Speaker Jason Frierson, D-Las Vegas. A couple of Republicans were also listed.

Nevada prides itself on a part-time, citizen legislature, although the separation-of-powers issue (along with some inherent conflicts of interest) could be resolved if the state had full-time lawmakers with no outside jobs. Yes, professional politics would certainly attract its share of grifters and self-aggrandizers, but Carson City is hardly free of them now.

Voters, however, have steadfastly refused to consider either a full-time Legislature or annual sessions. A common objection — the longer the Legislature meets, the greater the chance of bad laws — overlooks the obvious: Our current part-time Legislature has passed plenty of bad laws during the existing, limited sessions.

So, when bad times hit and special sessions must be called, the voters shouldn’t complain. They’re the ones who want things that way.

Contact Steve Sebelius at SSebelius@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0253. Follow @SteveSebelius on Twitter.