VICTOR JOECKS: The Nevada Department of Education makes the case to cut class-size reduction

The Nevada Department of Education is inadvertently making a compelling case for gutting the class-size reduction program.

To start, there’s good news about education in Nevada. From 2009 to 2019, Nevada’s fourth grade reading scores saw a statistically significant increase on the Nation’s Report Card. The average score increased from 211 to 218. The point scale isn’t intuitive, so for context, a score of 208 denotes a “basic” level of achievement. A score of 238 means a student is deemed “proficient.”

In 2019, Nevada’s fourth grade reading scores nearly reached the national average of 219. That doesn’t put Nevada in first place, but it’s not 49th either. For a state that’s understandably self-conscious about its educational system, that’s worth celebrating.

The natural question is, “What caused the increase?” In a presentation to legislators, which a consultant crafted, the department credits spending on a host of programs, with a focus on class-size reduction. The link seems logical enough — more spending equals better results.

But accepting that narrative requires an ignorance of the history of Nevada education spending.

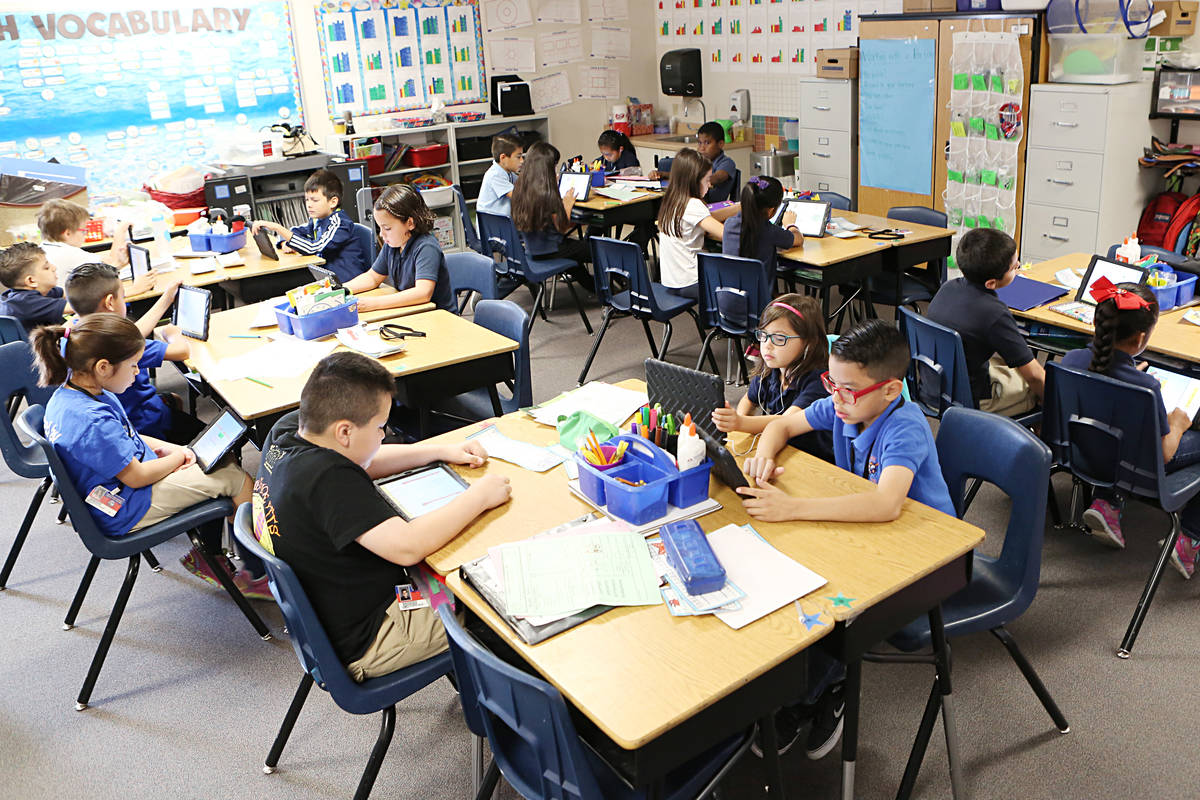

Nevada’s class-size reduction program started in the 1990-91 school year. The state has spent more than $3 billion on the effort, which focuses on early elementary classrooms. If class-size reduction worked, Nevada’s fourth graders would have seen results in the late 1990s, not 2019. Furthermore, in response to the Great Recession, the Legislature increased allowable class sizes in 2010, 2013 and 2015.

As the presentation notes, there’s an inverse relationship between class size and school rankings. The average class size in five-star elementary schools is almost 25. In one-star elementary schools, it’s 21. High schools show the same pattern.

The Education Department’s excuse is that class-size reduction hasn’t been large enough to produce results. That’s a typical bureaucratic attitude: “My plan failed miserable, so what we need is more of it.” The presentation contends that class sizes should decline by seven to 10 students to show results.

Nevada has already tried that. In the 1990-91 school year, the state’s first grade student-teacher ratio dropped from 25.4-to-1 to 16.1-to-1. The next year, second grade saw a similar decrease. But that didn’t produce learning gains. Here’s how Pepper Strum, a policy analyst with the Senate Committee on Human Resources, summarized a 1995 evaluation report.

“Academic gains appeared to be more predictable based upon student socioeconomic status rather than upon class size,” Sturm wrote in 1997. How little things change.

When you have a teacher shortage, class-size reduction creates an additional problem. Openings at high-performing schools often draw teachers from lower-performing ones. That means the students struggling the most are more likely to end up with less-experienced teachers or substitutes. That is currently happening in Nevada.

Further complicating the “spend more” narrative is that fourth grade reading scores increased from 2009 to 2015. That’s when the education establishment was complaining incessantly about mostly stagnant education budgets, which they labeled cuts.

The Education Department obviously supports class-size reduction. But its own statistics should reduce enthusiasm for that ineffective program.

Victor Joecks’ column appears in the Opinion section each Sunday, Wednesday and Friday. Contact him at vjoecks@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4698.