A poet resurrects Medusa for the modern age

At first, I thought the May 2022 release of Raegen M. Pietrucha’s book of poetry addressing sexual violence was well-timed, as the U.S. was still experiencing backlash against the #metoo movement. Then, in June, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, and the book seemed to resonate on an even deeper level as a response to the legal, historical and repetitive nature of misogyny.

But in truth, Head of a Gorgon, a chronological story told in poems, is timeless in its wrangling with an infuriatingly evergreen issue — predatory acts that strip women (though not exclusively women) of their sexual autonomy.

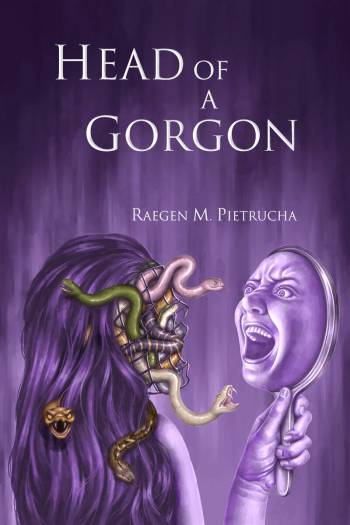

Pietrucha captures this timelessness by reimagining the sexual violence at the center of the ancient Greek myth of Medusa with emotional, physical and raw language. Her evocative imagery conjures intimate, personal feelings; thoughtful, philosophical questions; and rage. Plenty of rage. (See the book’s cover art by Jackie Liu!)

Pietrucha, 43, and now living in Florida, was an influence on the Las Vegas literary scene when she lived here from 2008-2019, and wrote much of Head of a Gorgon while here. She is currently working on a memoir based on her time in Las Vegas coping with a loved one’s gambling addiction.

After receiving her Master of Fine Arts from Bowling Green State University, she relocated to Las Vegas, eventually moving into a role at UNLV as the communications director for the Division of Research and Economic Development, where she edited the magazine Innovation. Meanwhile, she helped found UNLV’s undergraduate literary arts magazine, Beyond Thought. Throughout those years, she maintained a disciplined parallel focus on her creative writing. In 2015, she published an award-winning short chapbook, An Animal I Can’t Name, which introduces the themes she continued to explore in Head of a Gorgon.

Pietrucha’s new book gives Medusa a voice, and a past, and imagines her in conversation with various predators through her childhood, young adulthood and ultimately middle age. The ancient Greek myth has been told in countless ways, but here’s a quick recap: Medusa was a beautiful mortal who was raped by the god Poseidon, and subsequently the goddess Athena punished her by turning her into a monstrous Gorgon with hair of snakes and a gaze that turns men into stone. Later, Perseus cut her head off while she slept.

Already drawn to the imagery of Medusa, Pietrucha says she became more interested when her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, had a double mastectomy and beat the disease. “I started to notice the way some men would look at her, or would treat her, as if there was something scary about her.”

Pietrucha had been working on a series of poems about surviving sexual abuse, and when she combined the two projects, Head of a Gorgon was born. In it, she not only examines sexual violence, but the ongoing personal shame and blame pushed on survivors by society — echoing the story of Athena holding Medusa responsible rather than Poseidon.

“Medusa is a woman doubly punished, by man and woman alike,” Pietrucha says, “robbed multiple times over of any form of justice.” Gorgon is filled with lines that cut powerfully to the heart of such injustice. In a poem called “Hematologic,” Pietrucha envisions a resurrected Medusa reflecting on her wounds:

I was loved not. But isn’t the scar

worse than the raze that blazed it?

I’ve reflected on Head of a Gorgon’s passages a lot in recent months. At what I consider a culturally repugnant time, the book beautifully — if painfully — addresses deeply engrained and questionable social mores and gives empowering light to what have historically been the long periods of dark, shame-filled stigma experienced by many survivors of sexual assault. Pietrucha turns Medusa first into a contemporary young woman, and then works to allow her to be the hero of her own story, rather than forever a monster or victim.

It’s given me an insightful, artistic view of a horrendous subject. Whether a reader has survived sexual assault personally or not, the book broadens those themes to turn the ancient myth into a pertinent social commentary that seems, unfortunately, timeless. ◆

M’s Lesson at the Ranch

From Head of a Gorgon

By Raegen M. Pietrucha

What desert reminds me:

Secrets can hide from outsiders,

but not from my body—

its curves consumed by sand,

heels up to thighs, back,

and clinging sweaty to my neck.

What if I say more:

Cows don’t know

they’re fed fat

for slaughter.

Their calves

will forget them.

This knowledge won’t change

the patchwork of hide

and land that cloaks daily affairs

like the quilt you lie

over not under us, gnats

swimming in our humidity.

What desert reminds me:

Secrets can hide from outsiders.

But for how long? The hurts my mouth

blurts betray but don’t end your quest;

the sand is shadowing, turning a bolder

version of itself; you’re bolstered over

me, stained by sweat, sun, dusty stalks

of electrified straw. The sun falls and all

I can do is try to find something sharper

than the pain. Clouds above unravel

sky like hides ripped, revealing the red

of an animal I can’t name.

After, I sit in a tub

with no water.

Then I sit on a porch.

It’s morning once more.

A herd speaks from the distance.

Too far to see.

The land remembers its lot and feeds it.

The earth remembers its purpose, continues

to break beneath teeth.