An elegy for lost homelands

Kingston, Jamaica, rewards workers and schemers on Friday nights. The moonlight comes by 7 p.m. in mid-June. It wraps around the apex of the Blue Mountain before cascading into the harbor below. Flush with cash — money so pretty it could be from a child’s game — people head out into the softness of evening.

Hair gets straightened, sewn, shaved, scraped, braided, twisted, or gelled into styles that will withstand hours of joined hips gyrating in the humidity of clubs or dusty yards turned dance halls. Speakers boom-boom the bass of reggae dance music from various pockets of the business district. Cars cruise toward the city center, moving from neighborhood to neighborhood, each with its own sense of being and vocabulary. Later, couples will park on the hills above the city, their nakedness exposed to the arteries of lights in the city below.

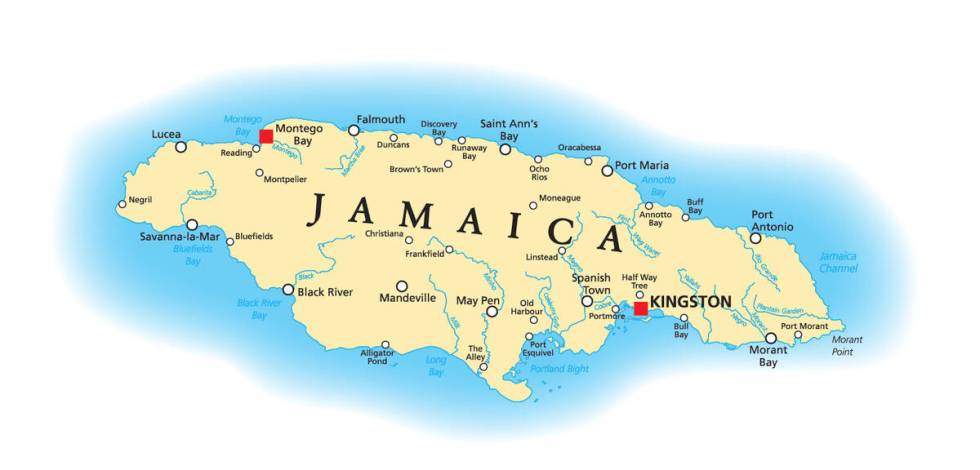

This is Jamaica’s capital and largest city; nearly a million people live here. But it does not sprawl: One could drive from Port Royal, where 33 acres lie underwater since a massive 1692 earthquake and ensuing tsunami, to the border communities in 10 minutes if traffic eased. If one could see the lights of Kingston’s soul, they would find a place where a faraway, bloated empire imposed its will on the land.

This is the first time I have been to Kingston, my hometown, since I moved back to Jamaica in May from Las Vegas, where I’d lived, with the exception of a brief hiccup in Provo, Utah, since 2013. For the past month, I’ve been living in the resort town of Montego Bay because I wanted quick access to the beach with American-style amenities. Now an editor of a literary magazine has invited me to meet a few writers at a duplex in the middle of Kingston. The place is hard to find; I drive by a desolate parking lot several times before deciding to trust my eyes instead of Google. In the dark, at the end of a bend, I find my destination. It is the only place on the small street. The security guard opens the metal gate to a graveled parking lot. A chasm of empty space looms between the parking lot and the garden. This area of Kingston is densely populated and highly desirable. I cross a bridge, a soribashi, the kind you see in Japanese gardens, while inhaling the faint cannabis smoke in the air.

A thriving network of artists, writers, and poets have been living the life I’ve mythologized. They work, write, make love, and spoil themselves in the rhythm of the tropical heat. Electrified by the recent literary work of the poet Kei Miller and authors Marlon James and Diana McCauley, the Jamaican air feels alive with promise and challenge. Writers don’t have to fling themselves too far away in order for their art to matter.

At a gathering under a clear night, Miller tells me that when he lives in the U.S., he often falls into the default of heterosexuality because he is a tall, athletic Black man. “But as soon as I step on a plane to Jamaica, everyone knows I am a battyman,” he says using the term for gay men. Being home in Jamaica allows him to shed any illusions of heterosexuality. There is something liberating in being seen, Miller says. I get it.

The venue, to the outside world, is a shoe boutique. On the weekends it is a haven for Bohemians and vagabonds with room and board available to artists. Plastic lawn chairs are placed close together under mango trees. I ask each person if they are the individual who invited me here: “Are you Annie?” A man tells me to narrow my inquiry to women only. I mumble something about gender being a construct and they laugh. This is my test to see if I am among people who believe everyone decides life for themselves. Their laughter tells me they are.

I swat at mosquitoes and pull my fan out though the air is cool. Dominoes slap the plywood tables before shuffling and clinking beneath wizened, brown hands. Annie is not here, so I head to a table that acts as a makeshift bar. Bottles of overproof rum are twisted open. A woman with an eye patch pours it freely and heavily into plastic cups. She hands me a cup and brushes my money away. I thank her and am surprised at my voice. I sound less like an American and more like the girl I used to be. My back straightens. My hips swing as if I’m carrying a basket of alligator pears on my head. It’s muscle memory. I am like the man returning home to the desert who instinctively shakes his shoes in case a scorpion hides between the eyelets. I am ready for something. Fight or flight. Love or war.

Ispent my childhood in Kingston. My neighborhood of Kencot was working class, and we looked out for each other. Our neighborhood seemed different than others, right down to the dust that clung like fine ash to the cheap furniture. For starters, Kencot was three streets: Kew Road, Crescent Road, and Grove Road. But it’s really part of a wider triangle that housed the phone company and two radio stations. Outsiders remembered we existed when they wanted to bypass traffic on the main roads.

We lived at 11 Kew Road. It was the norm to play cricket in the streets with bats fashioned from leftover wood given to us by the furniture makers at the corner. We would stop our games to direct lost motorists who confused our street with Little Kew Road. A man named Bugs kept order in our community by supplementing households with the proceeds of his passport and visa forgery. I remember him as congenial as he always asked about my paintings. My older brother Carl says I misremembered Bugs: “He was good and bad.” While Bugs would give people money to help relocate to America, he was also very fond of teenage girls.

Annette was a homeless woman who lived in the side- and backyards of whoever could give shelter for the night, but she mostly slept under our mango tree. Grown women tsk-tsked at Annette, hoping to evoke some sense of shame when her clothes showed evidence of menstruation. Men tormented her with crude comments. This made her angry. She would curse them only for the men to keel over in laughter.

She suffered from some kind of mental illness. But going to the only psychiatric hospital was a death sentence. My grandmother had died in the same hospital years before after wandering the streets in demented confusion. One night, men from outside our community — it had to be outsiders because Annette was very much one of us — raped Annette. She bore a child whom she loved with tenderness and abandon. When Annette’s daughter turned three, she was taken from Annette by the city. She could not contain her howls. The city soon came and took her away, too.

I knew the wider world was out there, and eventually I would need to leave my small island where I raced barefoot on our side streets trying to beat my older brothers home. It’s the place where I climbed mango trees, made traps for small birds, and watched kung fu movies back-to-back at the grindhouse. We’d dig holes many feet deep beneath our mango tree hoping to reach China. I stole library books and read them while walking in the street, oblivious to traffic. I was a quiet child at school because I was teased by students and teachers. I’d spend my school days wanting to be a ghost so I could slip unnoticed onto an Air Jamaica flight bound for New York.

Jamaica was my home, even as I bristled at the descriptors like “third world” or “developing nation” used to describe it. People called us poor, even as we ate farm-to-table and climbed the numerous waterfalls strewn about the island like Lego pieces on a toddler’s floor. I should have invested more of myself in the country. I should have relished what I had. I should have been a good student. Instead, I ditched lectures to cross the mighty Rio Cobre by raft and hike through old citrus orchards and train tunnels. The earthen red-brick facade of gambling dens frequented by pirates would leave its ancient trace on my palms; half a millennium had erased the origins of Port Royal’s moniker: “The Wickedest City on Earth.” Maybe I was always bound for a Sin City of one kind or another. Jamaica is where I hunted land crabs in the rainy season and dug through the muddy river banks to catch janga, the blue crawfish favored as an aphrodisiac. For 20 years, small island and city living was enough.

I was about to finish college, knowing the best job was a fast track to a dead-end, junior-management, tourism-related job. My ambition to live a Bohemian life free from the constraints of a conservative society could only be sated in America. I said goodbye to my family and friends and boarded a plane to New York City.

I’d spend the next 20 years unmoored in various parts of the continent. Every few years I would sell my furniture, carefully wrap a few mementos, and move to a different state. What I wanted was a sense of Kencot, first in New York, then in Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, Puerto Rico and — last and best — Las Vegas.

"Remind me,” I asked my husband in late 2021, “why are we leaving Las Vegas?” My husband and I often posed hypothetical questions and enumerated what we would do if we won the lottery or had a month to live. The thought of leaving America for a different life started out that way. Then, in September 2021, three years after I moved her to the States for dementia care, my mother died. I was suddenly free to make choices without thinking of her care. She’d left my siblings and me with five acres of prime grazing land on an aquifer in Jamaica without a will. My siblings didn’t want it, and I didn’t want what our ancestors had fought to acquire and cultivate after emancipation to return to nature or squatters. My path seemed clear.

But here I was, visiting the big why-are-we-moving question when we’d already decided to move. It was just a few months before I was supposed to leave for Jamaica. The children were fake-sleeping and I was in bed scrolling the neighborhood app, reading the comments, and looking for something to mock later on Twitter. We’d spent the pandemic with our eyes locked on a screen. Our inability to focus on the daily tasks at hand was exacerbated by watching people live different sorts of lives. It seemed like no one was telling the truth about our generation’s condition. Or maybe our generation’s condition was something different than we, tucked in our Southern Hills home, thought.

“I’m going home,” I’d say unsolicited to family and friends months before I left. They would politely oblige and ask why. I’d parrot some talking point read moments before on Twitter, maybe something about the expensive Las Vegas housing market. (This became more concrete when our landlord raised our rent by 16 percent.) Or, depending on what was trending, I might mention Lake Mead’s shallow water levels having a showdown with developers and the region’s population boom.

But what really worried us was the Great American 21st-Century Trajectory, with its unmistakable whiff of an aircraft with an engine on fire and a few screws loose. George Floyd’s murder left us shellshocked for days. Of course, this was happening in America. It had always happened in America. What made it sinister is that there seemed to be no escaping it. And we were, what? Casually deciding to move here and there as if we weren’t an interracial family with a Black son who at 13 was often mistaken for a grown man. Las Vegas’ diversity had narcotized me into believing we were approaching a post-racial world, even though we still had neighbors who would say things like, “I am OK with brown people.” America’s problems just seemed bigger than at any other moment in my lifetime. I’d tried to believe that with enough education and patriotism, I could bypass all the challenges Black people had to deal with. I wanted a break for my family, a chance to allow my children to be humans and take up the mantle, if they so choose, of liberation when they got older. It was a fine vision, but now it seemed like a delusion.

My husband sighed before launching patiently into the many practical reasons for leaving for Jamaica. My mother had left me enough land on an aquifer and a ready-to-use well to stay off the grid. We could escape the rat race. We could be closer to kin. We could slumber to the outdoor soundtrack of crickets and wake to the feathered songs of the ubiquitous vireo and yellow-chested spindalis announcing daylight. Their tiny claws wrapped around distribution electric lines unaware of the power surging beneath them.

Finally, my husband settled on the reason for moving I wanted to hear all along: “You can go home.”

Las Vegas was always easy to say yes to. At a very real level, it’s exactly what advertisers say it is — an escape into fantasy. Even those of us who live there often feel we can be anything with the right costume. I jibed with the vibe of the city because it didn’t pretend to be anything other than an ode to capitalism. It didn’t seem to care about any modifiers people brought to their identity. I don’t think anyone ever asked me the dreaded question, “Where are you from originally?” There was a quiet understanding that our memories often distort the past. The town rewarded those who live in the present.

My first visit to Las Vegas was working a transcontinental trip as a flight attendant for a legacy carrier. I’d been in the U.S. for two years and learned how to carry myself as an American. I wanted the Las Vegas of the movies. I sang “Viva Las Vegas” under my breath throughout the five-hour flight, thinking Elvis impersonators would greet me at arrival the way the Jamaica Tourist Board had folk singers in plantation attire fawn at tourists. The senior flight attendants, elegant blondes who modeled their look after Bo Derek and commuted from Scandinavia, seemed amused by my naivete. Las Vegas was a young place, they said. If I wanted to be amazed I should go to Greece or Turkey, where the buildings were older than our calendar. I didn’t care about ancient ruins. I could look at a thousand places in Las Vegas and fall into a stunned silence at the sheer imagination it takes to create a city out of desert dust. I wanted to be in a city that made such things, one without regard for sentiment and melancholy.

My next foray into the city was as the arm candy of a whale boyfriend. He would break himself away from the craps table for comped dinners. While he strategized backing his pass line and come bets, I pretended the setting was a reality TV show where I could only win a rose if my smile was big and wide. Las Vegas for me was limited to the Mirage volcano, spa, and concierge service. I believed the illusion casino employees spin that says everything is available if you only ask. Years later, I would crave a home city that wouldn’t think anything of a single, divorced mother. I craved familiarity and community. Las Vegas seemed plausible and would offer me that.

I rode into Las Vegas on a Tuesday in 2013 in my 20-year-old Volvo ready to start a new job as a flight attendant for an ultra-low-cost carrier. I chose the city as my base because I had met other single mothers looking for the kind of community often spoken of in small towns. One offered to babysit my young son while I worked. Another mom allowed me to stay in her home while my place was getting ready. Another acted as my life coach, helping me think about what I really wanted and chart a course for that life. It seemed kismet that two days after driving into Las Vegas I was invited to the annual Keystone Dinner at the Palazzo. Adam Laxalt and his wife sat to my left while the keynote speaker, Fox News personality Andrea Tantaros referenced stale jokes about Obama. I wasn’t partisan or political. I had been to both Democratic and Republican events over the years and in my experience, Republicans had the best food. You also get the best service when you are one of the only Black people. I wasn’t star-struck, but it impressed upon me that maybe Las Vegas was the town where I could live out my wildest dreams. I embraced it.

I wanted to reinvent my life. Not in a mommy makeover way, but one that could change the path of my descendants. Getting an American college degree was proof in my head of high culture and sophistication. I also thought an American college experience would ground me and help me decide once and for all my life’s mission. I went back to school with the intention to become a lawyer like one of my sisters. Unlike her, I did not have a high threshold for misery and billing on the quarter hour but I loved the research and writing. I had tried writing blogs in the hopes of making it a career but didn’t think it was something I could do. I only started to think of myself as a writer after a casual pitch of a story about the city’s Black cotillion was taken seriously by an alt-weekly. It would become the cover story. I only considered writing as a possibility when Lissa Townsend-Rogers, a writer I admired and tried to emulate, said I did a good job. I went on to get bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UNLV while diving headlong into writing for a living.

Las Vegas delivered my American Dream. I had work that fulfilled me. A family to sustain me and a community to care about. I dug deep into the Las Vegas culture in understanding the small things that matter, like calling Desert Inn “DI” and using Frank Sinatra Drive to avoid the Strip. I poured sips of brown liquor on the concrete at the corner where Tupac was shot. The Killers and Shamir became my hometown musicians, and wherever I went, I’d play their music to feel like home was close. When out-of-towners came to visit, I’d tell them “I am going to show you the real Las Vegas.” To me that meant hiking Mary Jane Falls, petting wild horses in Lee Canyon Meadow, gorging ourselves at Hoban Korean BBQ or Lotus of Siam and hitting The Orleans for a $3/$6 poker table. My life in Las Vegas, to paraphrase Jay Z, meant I could truly say, “Momma, I made it.”

I never wanted to leave Las Vegas. I rationalized the city as being separate from the rest of the country. A neon-purple, socially liberal place where money-green was the color that mattered. Las Vegas forgave and allowed those wishing to leave the sores of their history in the past. And few things brought me more delight than the desert blooms, wind-worn rock formations, and the unadorned blue sky stretching over the melting snow on Mount Charleston.

Life moves on, but sometimes you don’t; you play catch-up. I felt like that for a few years, although my new husband, baby and house seemed to say I was doing fine. Like Hydra, several maladies met me when I lived in Las Vegas. Before I was done processing one thing, another would pop up. My friend was murdered by her husband in front of her children. My father died without any of his children by his side. My mother’s dementia erased her memory of me. I turned 40, and the promise I’d made to myself to return to Jamaica by then was overdue.

It’s early May, and I am flying back to Jamaica at age 43. My mannerisms and speech indicate my Americanness, but the passengers can see through this facade. The woman seated in front of me makes her disapproval known of my permissive parenting. It’s something she wouldn’t do to an American. I do not reprimand the children as they play with the airplane’s tray tables. I do not cajole or threaten them with licks to sit in their seats. I ask them instead to tell me what they look forward to in their new home. I talk of the green rivers that run through the cities and the logwood blossoms that perfume the night. I tell them about the scalloped hilltops of the Cockpit country instead of admonishing them for their spilled apple juice. I am determined to preserve my civility even if I may be viewed as soft and foolish. I do all this just to impress upon the woman in front of us that I am both American and Jamaican.

The flight attendants make their landing announcements. I peek over my daughters’ heads to look outside the window. The dormant strength of the Atlantic Ocean hems the shallow blue of the Caribbean Sea. I can see the wind whip at the water below. I look at my two youngest children. My son and husband are still in Las Vegas as the school year winds down. They have a suburban house to pack. All the items we deemed necessary to live as a nuclear family. A month apart serves two aims: We save money on child care, and I can re-establish residency. The airplane wheels kiss the tarmac once, then twice. I wake the girls. The lush green of the mountainside above Montego Bay’s airport grants permission to imagine the future.

My eldest girl looks at me and asks if she should clap now. She recalls with a 4-year-old’s acuity the Jamaican traditions I’ve recently taught her. Clapping after a plane lands is how Jamaicans show appreciation to the flight crew. It’s almost mandatory participation, though I always self-muted out of defiance and embarrassment. That was back when I wanted to shed the small island for a bigger world. I modeled my identity on being an a well-traveled American similar to what I saw on TV. Today is different, since I am shedding my Americanness like a scurrying side-botched lizard. Now I see and believe the applause is for ourselves. We haven’t forgotten where we come from or who we are. I place my palms together. Clap. Clap. Clap. The sound drowns in the reverse thrust of the engine. The plane slows to a taxi and the landing announcement conceals my embarrassment. The applause never happens.

In the packed immigration hall, I am numbed by the overwhelming humidity. It’s hot for early May; the fans whirl while the air conditioning units buzz and blow. It does little to cool the heat ebbing from the bodies packed in from three or four flights. The room stirs. People keen on observations note that the foreigners are the ones with space between each person, tugging at their wet armpits and wiping beaded foreheads. I remember flights into Las Vegas when my fellow flight attendants and I would guess who was a visitor or Vegas resident. On flights where booze flows and bad behaviors surfaces you can tell the Vegas resident by the supernatural calm they exhibit. The Montego Bay airport is nearly the same. You can tell the Jamaican residents because they stand still and watch the people in the foreign line sway back and forth. I hunger for some immunity against being seen as a foreigner. My impatience fuels my sway.

The immigration officer asks how long I intend to stay on the island. “I am returning home,” I answer. I admit that I take an obnoxious pleasure in saying this, because it means I have options. There is no smile in her tone. She offers me the same casual hospitality Las Vegas cocktail waitresses give when guests at the slot machines are demanding. I want her to say something like, “Welcome back. We need people just like you to herald us into the new Jamaica.” Instead, she tells me with a perfunctory nod as she hands back our American passports that I have six months in the country and my children have three.

Living in Montego Bay has been an adjustment, but not a big enough one. It still feels plastic; I live in an area that used to be the garrison of the British Army. Their cannons and gunpowder rooms overlook the KFC, which casts its electric gaze on a manmade beach and park that had the original name of Dump Up. All the brands are here: Starbucks, Pizza Hut, Ace Hardware, Burger King and Ashley’s Home Furnishings. They do constant business even if you wait twice as long for food or have a limited selection of beige and brown furniture. It’s not America’s best but the best that we can imitate. The city fathers are molding Montego Bay to look like a version of Jamaica palatable to Americans. The landscape resists. The limestone crags make symmetrical neighborhoods impossible. The jungle vines creep overhead even when developers pave the grounds.

When I left Las Vegas, I took my mother’s ashes with me. Now I stop in Kingston as part of the long journey to the rural farming community where her people had settled after emancipation. It was her wish to be buried in the same seaside hamlet where she was born. It was her last bit of resistance to what she saw as the impossibility of assimilation. Land is forever imprinted on you, even if you don’t admit it. As a woman born under British rule in a country that fought for centuries for liberation, she was pained to see us leave Jamaica. She would tell me her dream was to have all of us on the island together, living in the same area. Even though she loved America, she was very firm in the belief that America was where you went to work and make money. You lived on the land where your umbilical cord was cut and buried, forever tied to a place.

My childhood house in Kingston is built in the British colonial style, with a large L-shaped veranda facing a large front garden. The home was never big, and we spent most of our time on the veranda or climbing the mango tree laden with ripe, dark-green fruit. On my arrival, I find that my childhood house, just like my mother’s childhood home, is no longer standing. Both places have long been replaced by rubble and broken glass. Only the cellars and a vague outline of where things used to be remain. As I walk around the grasping concrete and caved-in wooden floors, I’m surprised by my lack of sentiment. No wave of grief washes over me, though I try to force myself to feel sorrow. Instead, I feel dolorous for lacking the right feelings. I’d hoped to have some elegy to offer my mother.

Standing on the back veranda should give me a sense of comfort, but I realize the security I’m seeking is false. To have a home means at some point you belonged somewhere. But here, the rubble reminds me that home can be as much an imagined place as a physical one, and both the physical and imagined are subject to change. I lived on this plot for my first 16 years, but when I think of a home that offered me an emotional connection, comfort, and stability, I conjure Las Vegas. I relive the feeling of possibility when driving from the Red Rock end of Charleston Boulevard to the eastside Mormon Tabernacle before dead-ending at Frenchman Mountain.

Metaphysically, I am a Gemini, belonging to neither Jamaica nor Las Vegas. Jamaica, a dot of an island in the Caribbean Sea, with its multitudes of rivers and streams elevates and grounds my heart and mind. But Las Vegas is where my body took flight, emerging from a cultural cocoon of conservative views. Both places made me who I am. Leaving one for the other renders me incomplete.

Heraclitus said no man ever steps in the same river twice, because few things stay constant. I’ve always experienced wanderlust, so I wandered. And now this home, my Jamaica, is seen through my new and inconstant eyes. Even the air feels hotter and the energy more impatient. We are remade by our experiences and discoveries. Our view is from a different headspace. I am certainly not the girl who grew up here. ◆