Desert ink, streaming: ‘I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness’ from page to screen

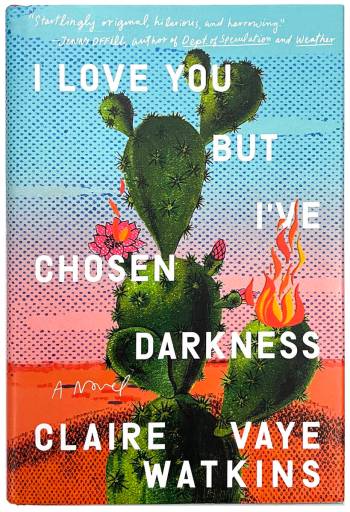

In Nevada-born author Claire Vaye Watkins’ latest novel, I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness, Watkins’ protagonist, a successful writer named Claire Vaye Watkins, leaves her husband and newborn baby to embark on a journey of self-discovery, returning to her roots in the Amargosa Valley west of Las Vegas, where she grew up. The novel excavates Watkins’ family’s history. Her father, Paul Watkins, was a member of — and later testified against — Charles Manson’s “Family”; her mother, Martha, was a Las Vegas-raised writer and artist who founded a museum in Shoshone.

Now the novel is being adapted into a television series by another literary star with Nevada connections: Alissa Nutting, who was a fellow at Black Mountain Institute and earned her Ph.D. at UNLV. Nutting is the author of the award-winning short story collection Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls and the novels Tampa and Made for Love — the last of which has been adapted as an HBO Max television series.

While the Watkins-Nutting collaboration is still in its early stages, it has the backing of a seasoned team in the streaming TV game: Nutting’s co-executive producer on Made for Love, Stephanie Laing, is slated to direct I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness for Tomorrow Studios, the studio behind such hits as TNT’s Snowpiercer. Laing was also executive producer of Tomorrow’s popular Physical on AppleTV+.

I recently caught up with Watkins, now a professor of creative writing at the University of California, Irvine, and Nutting, a Los Angeles-based screenwriter, for a conversation about motherhood, the desert, Las Vegas and the perils and pleasures of adapting work from one medium to another.

How did this novel come together for you?

Watkins: Well, I had a baby and was kind of taken down to the studs on a spiritual and artistic level. I wrote my first two books — the story collection (Battleborn) and my first novel (Gold Fame Citrus) — before she was born. It seemed like the process of bringing her into the world changed everything for me. So I was sort of molting, you know. I was like, “I don’t know what I write or who I am right now.” The first thing I wrote was a response to a postpartum depression diagnosis. “Well, that’s your word for this,” I thought. “What would be my words for it?” I realized, well, if I’m gonna find the language for this, I have to start way back, like way back — at least when the bombs started falling on the desert, and then go into my parents’ life and why things are the way they are.

Talk to me about the television adaptation. How how did this come together?

Nutting: It was really funny, because I’m a mother, and one of my good friends — a director I’ve worked with before, Stephanie Laing — is a mother. And one of the things you can already intuit, even if you haven’t read the book, just from hearing Claire talk, is this generous honesty that feels incredibly affirming. There are so many primal feelings and thoughts and instincts that motherhood brings that are outside the public conversation. Stephanie and I had bonded in conversation talking about these experiences prior to Claire’s book. Then she called me one day and said, “Have you read I Love You —” And I finished her sentence for her: “— But I’ve Chosen Darkness.” Yes! I love her writing so much, not only the exquisite narrative potential that Claire has opened within the novel, but also Stephanie and I have a shared love of the desert. And we hadn’t seen it made into a love letter to that land. Until I read this book, I really never thought of the desert as a metaphor for motherhood, because the metaphors we have for motherhood are incomplete and false. And I think in an equal way, the metaphors we have for the desert are incomplete and false.

Watkins: Someone described it — someone who probably hadn’t read it all — as “Oh, this is a story about a woman realizing she doesn’t want to be a mother.” No, no, no, not at all. It’s about letting go of all of the received expectations and all of the garbage that comes from growing up in a culture that doesn’t worship the creative act of making another human being … or the creative act of writing something. Our society is not interested in supporting mothers or supporting our artists, so doing it is such a miracle.

In the process of writing this novel, did you discover anything new about your parents?

Watkins: There was a lot of discovery. That’s why I started writing it, because I didn’t know them. My mom died when I was 22, and my dad died when I was six. So there’s much more I felt like I didn’t know, especially as I was embarking on motherhood, and I had no way to reach them on this earthly plane.

This is basically my version of a séance, just like going back and using their words, seeing how they tell their story. Luckily, I really was sent this cache of letters, so that helped a lot in seeing what it was like for my mom to grow up in Vegas in the seventies. You know, they were both really good storytellers. My mom was in AA, and Alcoholics Anonymous was a pretty central part of our scene. It was like our church, and storytelling is really important there. If you don’t get real with your stories, you’re not gonna get better. So I benefited from her wonderful storytelling my whole life. But I never knew her before she was a mother, so to hear her talk in these letters about growing up on the west side of Vegas … she was exposed to a lot of sexual violence and the threat of it was just everywhere for her. And it was just overwhelming to read.

How much did you two know about each other before this collaboration?

Watkins: I’ve known of Alissa for a long time, and have always thought of her as, like, kindred. But we hadn’t actually known each other.

Nutting: In Vegas, I would have kind of conversations where I felt like I knew you because other people who knew you were talking and there is this aspect to your work where the reader feels, um, a pretty intense pull. One of the first short stories I read by Claire was about mole people (laughs). I just thought it was so beautiful and loved it so much, you know, and kind of like instantly knew this was a mind and an imagination that I wanted to hear talk about anything at all. So imagine my luck when we happened to have these overlapping circles in our Venn diagram.

Claire, how do you feel about letting other people — like Alyssa during this adaptation — dig into your work and transform it?

Watkins: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I already wrote the book. It’s in ink and papyrus. I feel I said my piece about it, and now I feel like I can surrender it. And doing that with Alyssa is special. I always felt like I was in good hands, and there was just a person who had experienced the land of Southern Nevada and the wider Mojave Desert as I had. I felt like, “OK, yes.” That was important. The really important thing for me: Whoever adapted it could not think of the desert as a wasteland. That could be a part of it, that could be like a dimension of it, but it can’t be the whole deal. That just wouldn’t be even worth doing. So it’s been pure joy and excitement. I wanted this book to let me take the reader on this road trip in the American West and look at someone who is trying to take spiritual nourishment from the land, but is also aware of all of the defilements being done to the land. Visually, I think that the film will be better, way better, at getting at that part than I could possibly have with words.

Claire, did you ever tell Alyssa, “Hey, whatever you do, make sure this scene stays in”?

Watkins: No way. I would never do that to a fellow artist. If someone tried to do that to me, I would just be like, Are you kidding me? It’s like, you know, like Tonya Harding-ing their knee or something. No. But I don’t have to because I know that this team understands.

Alissa, how has your time in this community — Nevada, the desert, Las Vegas — informed you in your work?

Nutting: Oh, hugely. Like when I tell people that I got my Ph.D. in Vegas, they think I’m making a joke, and they laugh. Then they realize I wasn’t joking and try to talk their way out. For me, there really wasn’t a better place for it. I keep going back to multitudes: Vegas is so many things at the same time. I never felt the need to be anywhere else. Everything you see is so right-on at every single level. It’s so hyperbolic in a way that I think is profoundly truthful. Things are above-board in a way that they aren’t in other places I’ve lived.

Watkins: I feel blessed to have come of age as an artist in Southern Nevada. It’s just such a rich, vivid education for a storyteller, and for many of the reasons that Alissa’s saying, it’s more honest. It’s like, Yeah, this is about money (laughs): money, money, money, sex, having a body. And I have always enjoyed the marginality of the frontier outpost. Even Brigham Young couldn’t get people to stay down in Vegas, you know? They were like, “No way!” So, I just feel really grateful to have been a daughter of that place. ◆