Las Vegas, the Super Bowl, and the mixed blessings of the big time

Las Vegas, as I once knew it, was like the kid in the 1988 film Big, forever on the edge of adolescence and dreaming of growing up fast. In the film, 12-year-old Josh Baskin stumbles upon a mystical, mechanized carnival attraction named Zoltar, makes a wish and, boom, turns into a handsome, if not strapping, young Tom Hanks. In quick succession, the newly big, or big-ish, kid becomes a sensation in the corporate toy biz, shuffles right up to the edge of an age-inappropriate relationship, and realizes that being big is really complicated. Then he wishes himself back to the simpler life of a preteen.

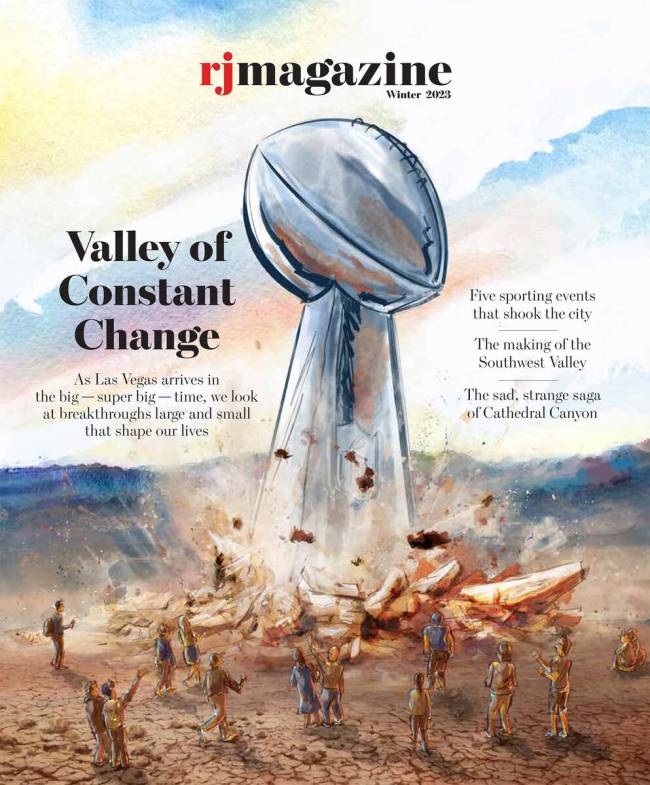

For our city, though, there is no going back. We are now a Super Bowl town, a Formula One town, a town whose iconic properties are owned not by local magnates but by global capital. A town that has gone beyond building freeways and now specializes full time in rebuilding freeways. A town where the landlord of your rental home isn’t the family across the street but the opaque holding company on the other side of the world.

When I was growing up — and it sounds like it was a thousand years ago, but it wasn’t; Las Vegans live in dog years — Maryland Parkway was the center of the local universe. Buildings that were not hotels or hospitals were pretty much never more than two stories tall. And every third lot on our our big local arterials — Flamingo, Tropicana, Desert Inn — was a vacant patch of raw desert, occasionally occupied by a tiny abandoned shack that I convinced myself was the former residence of a real cowboy. For kids, the lots meant lizards to catch and mounds of dirt to conquer with BMX bikes (fortunately, the distance from the lots to, say, Desert Springs Hospital was never far). Such a lot was behind my house, and behind the lot was a ranch with buffalo.

Where was this far-flung, rustic spot? Well, it was just off Flamingo and Sandhill, not exactly the edge of the world even then. It’s just that Las Vegas was a checkerboard of nothing and something — and all of those patches of nothingness were somehow thrilling in their promise: What would they become? What would our city look like when it was big? Would we miss the nothing? Was “nothing” really nothing?

During the long years of childhood — years were longer back then — I fell in love with UNLV basketball at the Convention Center rotunda, then followed the Runnin’ Rebels to the Thomas & Mack Center. The teams were thrilling, always pounding at the doors of the Big Time on behalf of our unruly-kid-brother town. Those pre-Larry Johnson Rebels taught us what it felt like to step up to the threshold of the civic dream of bigness and fail to get through the gate. I’m here to report that it felt weirdly good, in that perverse, bittersweet way that the darkness of The Empire Strikes Back felt good: Not yet, young Vegas, not yet. And we told ourselves how great it would be on the other side … when we were big. And we wished.

Las Vegas has now sped past big and is bound for huge. And it feels — well, I suppose it’s not for my generation to decide. So I’ll leave it to you to read our winter Breakthroughs issue, filled with stories of a blossoming, quaking cityscape full of new triumphs, new wonders and new anxieties, and ask yourself: Should we have been careful what we wished for? ◆