The Great Western Sketch Tour

1. Wasatch

From time to time my work as an architect allows me to travel the country, and one of my favorite places to visit is Salt Lake City. For me, these trips are a homecoming. I was not born here, but I was raised in this valley, breathing its cool high-desert air, encircled by its snow-dusted mountains.

Each time I return, my mind and senses are flooded by memories of bygone days, people and events. Something about the hue of sunlight that falls upon the greens and browns of the foothills on a midsummer evening evokes a longing to return to a time tucked away in the far reaches of my mind.

Images return to my mind’s eye, more vivid than they were at first sight. I sense the sounds and smells of my youth. Those crucible days on the way from adolescence to adulthood! That patchwork quilt of moments into which life stuffed the substance of a self. It was the 1990s; everything seemed possible. God, Family, Love and Tradition mixed together like the scents wafting from the kitchen at Thanksgiving. The Wasatch Range and the azure dome of the sky combined to create architecture of the highest order: a place where I would gorge myself with the sweet fruit of possibility.

On any given summer evening, I would watch a fly ball rise into the gloaming of the fading day. I would sprint full-out to intercept its arc before it touched the earth and as I belly-flopped face first into the dewy outfield grass, my nose would fill with the scent of dirt and leather and turf, and my lungs would fill with the warm and moist summer air. Far from my mind, the thought that one day this moment would end and that the great responsibilities of adulthood would impose themselves. Those nights I only knew the passion and drive to succeed; the mountains stood silently by and watched as I learned what I could achieve.

The summer roads in the valley of the Great Salt Lake are littered with roadside stalls selling sweet corn, peaches, strawberries and, oftentimes, sno-cones. Each August, the summer begins to give up its fight, the sweet smell of the Russian olive trees mingles with the woody smell of the elms. In my mother’s garden, the breeze carries the sound of children’s final summer laughter. These moments are long gone, but not really. I remember. I remember that there is strength in these hills, that they are everlasting and firm and steadfast. I remember that no matter the place where my head lays down to sleep, those mountains are a part of me, those qualities and traits I learned here in this valley are the greatest of the great things I have done and am. I remember that what filled me, from my earliest days, were the strong enduring things of this world. The sense of granite, oak, pine and shale: simplicity, honesty, hard work, devotion. A dedication to God, family and home that transcends questions of time, distance or circumstance.

I remember …

2. The Gift

I remember the feeling of a size-10 leather work boot as it firmly struck my backside. As I flew through the hot summer air, my 7-year-old brain knew that this was a kind of trouble I had not been in before. In quick succession, I watched my two younger brothers also get picked up by the waistband of their shorts and given a swift kick in their rears. It was a move that a 65-year-old man — a stranger no less — could get away with in the 1980s. And so my brothers and I were unceremoniously sent home. We would certainly think twice before we climbed on the roof of that chicken coop again.

My family had recently moved to a new home that backed onto a couple working farms in the Salt Lake Valley. Curiosity and summertime boredom led my brothers and me to investigate the barn and chicken coop located less than 100 yards from our back door. Despite our unique introduction to Bill Moore, he became one of the more central figures of my childhood. Bill was a hardworking former Air Force man who was just beginning his retirement years on an 85-year-old family farm. He had never married and worked the farm alone. We soon filled his afternoons and Saturdays with our adventures; and he in turn filled our lives with his time and his love.

Bill’s farm was soon known by all the neighborhood kids as a place you could go to fix your bike. If you were interested, you could learn how to pick apricots and then slice them and dry them into fruit leather in a homemade food dehydrator that was powered by the sun. We learned about car maintenance, tractor maintenance and how to tend a garden. In later years, we learned where the cows really went each fall and why new cows came back in the spring. As we grew stronger, we learned hard work baling alfalfa and bringing it back into the barn. Bill was soon my mother’s favorite human; he had the ability to entertain, educate and tire out her seven kids. It didn’t matter the season — there was always fun at Bill’s farm.

When I was 16 years old, our family was facing the dreaded prospect that we would have to move out of the neighborhood and away from our favorite farmer. Due to financial misfortune, it seemed there was no possible way to make things work out so that we could stay. Enter Farmer Bill, hat in hand, asking my parents if he couldn’t give them three acres of his farm that they might be able to sell to pay for a house. My parents accepted the offer, sold the land to a developer in exchange for a home that backed onto the farm they loved so well. I even spent my last two years of high school living on a street named after my baby sister.

The gift was larger than life. The house was humble but sufficient. My mother always called it her dream home. It was the only home she would ever own. She passed away in the master bedroom of that home. She was followed a few years later by my father and, in quick succession, by Farmer Bill.

The farm is now gone. A church and a housing project have replaced it. The home still stands, although occupied by a new family. Sometimes when I am in the area, I will drive to see the greatest gift I have ever known. I notice how the trees I planted with my mother have grown so tall. I marvel that the lawn and irrigation system my brothers and I designed and installed is still functioning 25 years later. The home itself has become more metaphor than sticks and bricks. This home is charity — or pure love. This home is the pinnacle of human empathy, friendship and selfless concern for others. It is not something that can be designed with blueprints or capable use of power tools. This type of structure is only built by love.

3. Buildings of Sacrifice

Ninety minutes of northbound driving along an ever-more-crowded Interstate 15 carries me beyond Utah’s capital city and through the narrow neck of land wedged between the mountains around Bountiful Peak and the Great Salt Lake. The urban expanse along the Wasatch Front gives way to farms, fields and desert, and I emerge into a strand of small agricultural communities bound by old Highway 89 and the Bear River. Here, in the far reaches of northern Utah, Smithfield and Brigham City sit on either side of a mountain. Once farming towns, they are now bedroom communities that feed nearby Utah State University. Both are homes to buildings and histories that should inspire us today.

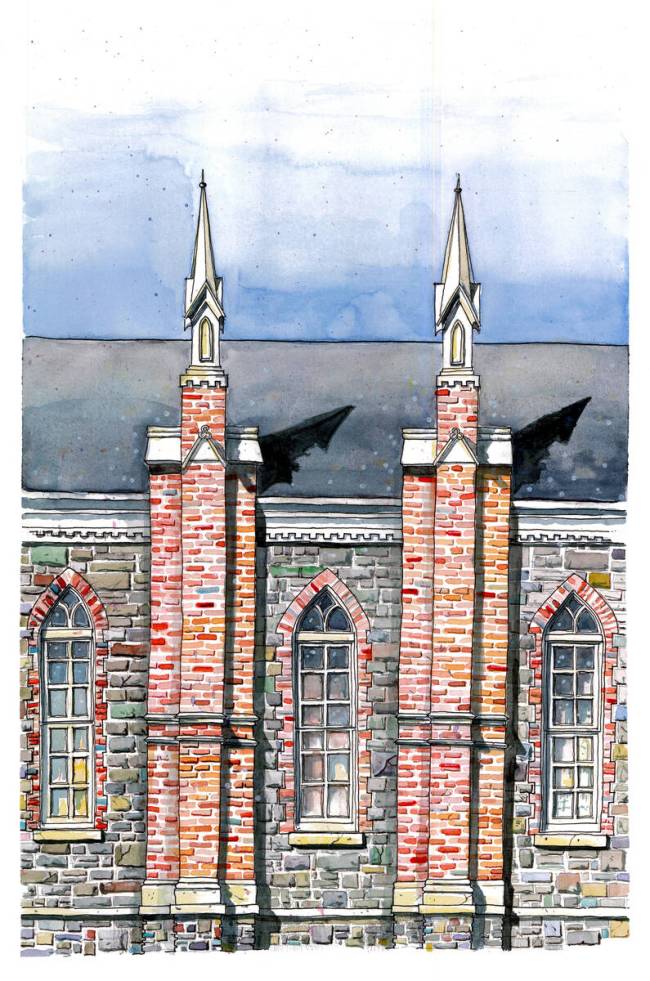

The two towns were established in the mid-19th century by Mormon pioneer families. Brigham City was founded by 50 families in 1851, and Smithfield by three brothers and their wives a few years later. By 1865, Brigham City had nearly 1,000 residents and Smithfield just over 700. Both communities almost immediately began building large tabernacles of stone and timber while a number of their residents still lived in dugouts and wagon boxes.

Why would a bunch of sugar beet farmers endeavor to build stone Tabernacle buildings when a wood-framed worship space would have done the trick? Why embark on a project that would end up taking more than 20 years at a cost of almost $2 million in 21st century money? Why spend so much on this singular church when their own homes were so meager and humble? Why spend so much on this community edifice when their own budgets were so tight? Why indeed.

Maybe these questions help us understand what it means — and what it takes — to make a great place. Perhaps sacrifice is a requirement of great place-making. When I look across the West and travel through communities large and small, I can see the buildings and places for which communities have sacrificed — the ones that meant the most to them. The intentional sacrifice of time and treasure by community residents is worn as a badge of honor on these buildings. Personal sacrifice for the future of the community is a fading American value. Our modern community buildings are realized quickly and efficiently. Indirect financial investments are still made through taxes, but the sacrifice is incomplete and far too convenient. We are robbed of the opportunity to imbue these buildings with ourselves when we lose the ability to sacrifice our time.

Spend some quiet time in one of these old western tabernacles and you’ll start to sense the stories of the people who made these places. Stories of women spending long hours making the readily available pine look like more expensive and harder-to-find oak. The women wielded hair combs like primitive paintbrushes; with an expert creative touch realized by repetition, the teeth of the combs would swirl across the wood surface, the lines of dark stain implying the grain of oak. There are stories of farmers spending days in the field only to come and spend the twilight hours and weekends working on the Tabernacle. I’m sure there were some who started the work and never saw it finished. A 20-year build is a long time. I am still sure that they worked with a happy heart and the knowledge that the labor was its own reward.

I often lament that our busy lives today leave little room for these great communal opportunities to sacrifice as one for the common good. We lose an opportunity to create something great. We often are so wrapped up in the importance of our own lives that we miss the splendor and lasting magnificence that can be created by inspired human hands, even the hands of a thousand simple sugar beet farmers in the twilight hours of their work days.

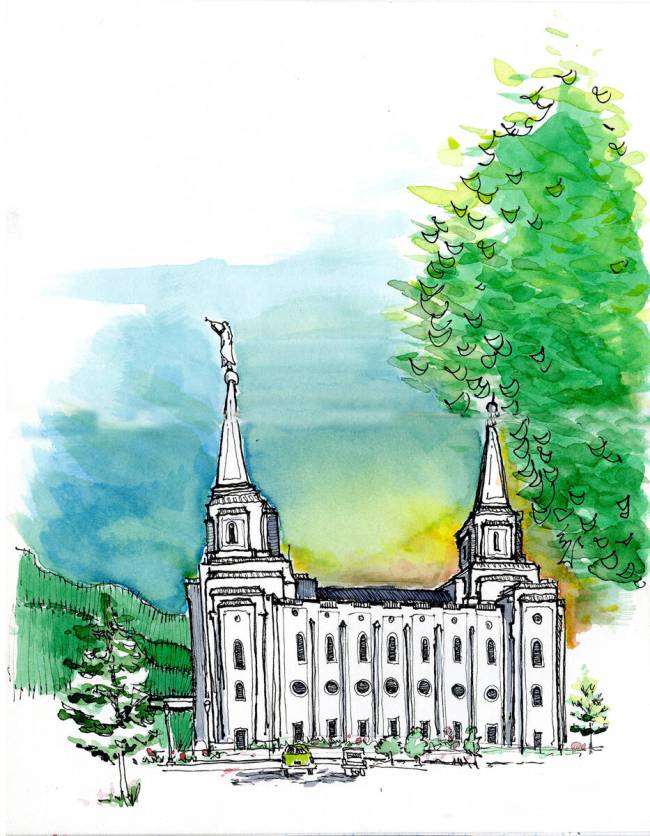

4. Steeples

In Brigham City, I stop along the road to enjoy a taste of the fresh fruit that fuels a booming local economy each fall. Cherries in a cup, copiously mixed with local ice cream. Heaven. My eyes are drawn to the crystalline white twin spires of the Brigham City temple. The steeples get me thinking about our gestures, ancient and modern, toward the sky. I can’t help seeing them as signs of hope.

The act of designing and building steeples is indicative of communities that aspire — there’s that word, “spire” — to a consciousness that reaches beyond the gravity-and-time-bound here and now, to a sense that something within us also resides in the past and the future and in realms still unknown. Steeples embody our hope for things better than current circumstance. No matter the meanness or simplicity of the building attached to the spire, these architectural structures point ever upward, prodding mankind to look beyond the baseness and squalor at its feet and raise its eyes and minds to the heavens. In many cultures throughout the world, the city skylines are dotted with vertical architectural elements that serve to lift mankind’s gaze upward to the heavens.

In early American culture, the city was built up around a church or around a steeple. Communities adorn these spires with clocks and bells that serve to remind us that our time here on earth is limited and as an auditory reminder of places and beings greater than ourselves. I have never made my home in a community where a spire was not somewhere near the heart of the place. Sadly, in recent years many religious structures have eschewed these beloved vertical structures.

With a singular skyward gesture, these spires beckon us to come and see. They stand through rain, through snow, through wind and heat. Whether or not you believe in the canonical vision of heaven, spires direct your gaze to the heavens, the elsewhere that shows both our smallness in the face of creation and the extraordinary privilege of being alive, here, now. They plant a flag of faith for the faceless generations who believed in something higher and yearned to be something more.

5. Mining Towns

Eastward, northward. Along Interstate 70 I push onward into Colorado. I am loosely headed for the high mountain valley on the eastern slope of Mount Elbert. Home to Colorado’s former capital city in Leadville. Having no agenda for my journey, I picked a two-lane road that forked from the main highway a few miles east of Vail. My little road wound through pines and aspens. It hosted a journey past rivers and streams and snow-dusted peaks. For more than an hour, the road and I ascended the slopes of the Rockies and climbed toward the heavens. Certainly I must be nearing the limits of the atmosphere. I’m amazed to crest a hill and find myself on the doorstep of a mining town. I reach for my sketchbook and pen.

Experiencing the rural mining towns of the Rockies is like participating in an Irish wake for a time not so long ago. Modern society has declared the subject deceased, yet the celebration and revelry for the life that was created here is palpable. The body of the deceased stretches out before you as a patchwork of beautifully aging and antiquated buildings crudely “made up” with modern conveniences — “progress” roughly applied over the beautiful natural features of great architecture. The contrast is glaring, as if draping these buildings with wires for cable TV and internet service was always the rouge intended for these cheeks.

Over the decades of the 20th century, some of these towns have been reborn as resort cities. Others remain locked somewhere in the detritus of history. Driving into a town that stood its ground against the gaping abyss of modernity almost always inspires a feeling of all-American pride within me. Those towns that seem to be frozen in another day and time are the only places I have found that feel authentic and real.

Perhaps what I am really saying is that these old towns resonate with a place inside of me. Something inside of me feels real when I am there. Something feels real when I draw these places, think of these buildings and imagine for a moment what stories they might tell us if they could. These places somehow stir memories from a time I can’t remember on streets I’ve yet to walk. Perhaps there’s some revenant ancestor within me scratching at my architect’s heart and asking for a voice. Maybe that’s the truth within all of us and the truth of the family of man — that we are fated to carry the memories and yearnings of all our ancestors’ individual and collective pasts in our hearts. We wander this life with much older hearts, and certainly much older souls, than we know.

I walk the long blocks north of Main Street in Leadville. A yellow house flanked by creaking pines catches my eye and begs my watercolor brush to remember it in my sketchbook. As I sketch these colorful houses — and they are colorful, a riot of color sits at the back of the curb along each street in mining towns — I wonder about the decision that led to those color selections. Could it be that the colors are a response to age and everything in town slowly getting covered in soot and ash? I imagine a splash of color was probably seen as an opportunity to push the sun back up a little higher into the sky and extend the life of things for a while.

I wonder these types of things as I draw these homes: I often wonder about the children who ran out those front doors on summer mornings or winter afternoons. Were they happy? Where were they headed in such a hurry? Were they, in fact, sad or scared? Did they have friends, or hopes, or aspirations bigger than these towns? Somewhere back in my lineage, I’m sure I had a younger version of a great-grandpa or a great-grandma who ran out a front door like this. Where were they going?

I’m sure if I listen, or better yet, if I look, I can see a hint of some ancestor in this drawing. That talent passed somewhere through time, lineage and the cosmos. For whatever purpose, the talent was able to span the chasm of generational gaps and reach through the ether from the unknown to me. I feel my ancestors in such places.

Do you have places where the past speaks to you, where it is stirred to speak from within you? Is there someplace where you can, more clearly than usual, hear your grandparents in your laugh, see them in your smile? Where do you feel connected to the worlds that are lost … but never really lost? Where do you suddenly become aware that you absentmindedly twirl your hair with your finger, just like your grandma did? Where did your knack for mechanical things come from? Did it come from these people, in this place? What is the origin of your way with words?

Look and listen; the roots are there. You’ll see them in the mirror. You’ll hear them in your own voice. Sometimes you just need to get to someplace quiet enough to hear. ◆