EDITORIAL: DMV cost overruns highlight systemic flaws in state contracts

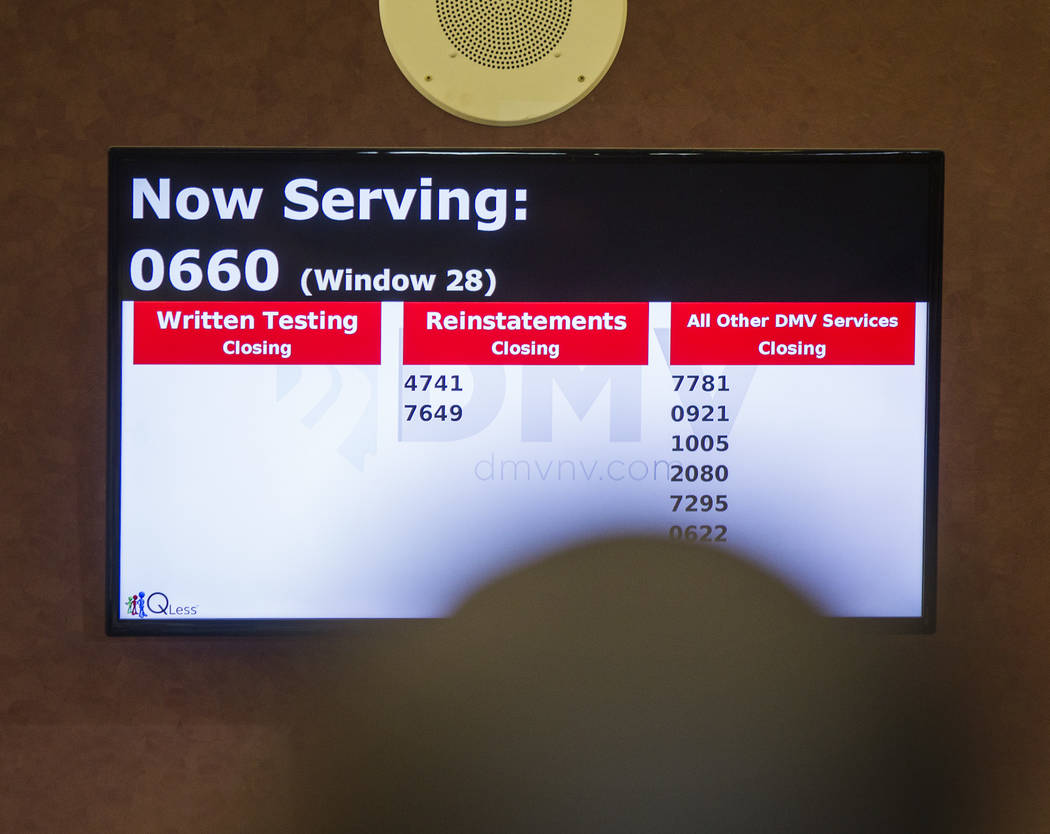

Long lines aren’t the only problems plaguing the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles.

In 2015, Nevada imposed a $1 fee on DMV transactions to pay for upgrades to the agency’s computer system. The pitch was appealing. The new technology would allow drivers to complete many DMV transactions, such as taking a driver’s license photo and registering titles, from home.

Four years and $31 million later, however, Nevadans still must physically go to a DMV office to complete those tasks. That’s because Tech Mahindra, the company Nevada hired to complete the $75 million project, failed miserably. Nevada officials fired the company last year and now believe they can salvage only equipment, hardware and software worth $4.5 million. Even for the public sector, turning $31 million into $4.5 million is an impressive level of failure.

And as the Review-Journal’s Art Kane uncovered, there may be more to this failure than run-of-the-mill governmental incompetence. Troy Dillard worked as the DMV’s executive director in 2015. He testified in favor of the $1 fee increase. He told lawmakers that the DMV had strategies in place to “mitigate or eliminate” any difficulties the project might face.

Mr. Kane uncovered records showing that Mr. Dillard oversaw the process of soliciting bids for the project. Nevada’s “request for proposal,”which outlines the parameters expected of those seeking the contract, had a seemingly odd requirement — that bidders use specific Oracle products. Mr. Dillard also had approval over members of the board that determined who would get the project.

Before the DMV awarded the contract, however, Mr. Dillard retired. That was October 2015. The following February, he began working as — surprise! — a senior vice president at Tech Mahindra. During that same month, Tech Mahindra was negotiating with his former DMV subordinates on the project Mr. Dillard once pushed for. That turned into a $75 million contract for Tech Mahindra, which was $13 million higher than the company’s original bid.

This should raise large, bright-red flags, especially when you consider the insistence on Oracle products. “I recall people saying it was an Oracle product, and that kind of put Tech Mahindra ahead,” Shannon Berry, former state assistant chief procurement officer said. “It gave them more points.”

On projects such as these, Nevada selects the best bid, not necessarily the lowest bid. Dell submitted a bid of $36 million with some additional costs for subcontracting. But it lost out to Tech Mahindra, which received the highest marks for IT qualifications and the most total points.

Three years later, the folly of that decision is obvious. And thanks to a $166,000 taxpayer-funded review by an outside consultant, you can see the incompetence started at the top. The DMV selected an “unproven” technology and didn’t implement basic project management controls.

So either DMV leadership is woefully inept or Mr. Dillard used his position to steer a $75 million contract to a company he not-so-coincidentally took a job with after “retiring” from the agency. Or both.

It’s also worth noting the role Nevada’s overly generous Public Employees’ Retirement System played in this fiasco. Mr. Dillard retired when he was 49, about 10 years before a private-sector worker could withdraw penalty-free from a 401(k). Mr. Dillard started collecting his $96,000-a-year taxpayer-guaranteed pension immediately. If Mr. Dillard hadn’t been able to collect his full pension until 60 or 65, perhaps he wouldn’t have had one eye on the job market while the DMV was seeking a vendor. Yet another reason to reform PERS.

This isn’t the only high-profile state contract that reeks of insider trading, of course. In 2017, then-Sen. Majority Leader Aaron Ford snuck through a provision removing the cap on how much a private law firm may earn representing state government. Then, as attorney general, he reversed the decision by his predecessor and decided to seek outside counsel for the state’s opioid litigation. Mr. Ford recused himself from the selection process, but to the surprise of no one, the AG’s office awarded the contract to Eglet Prince, Mr. Ford’s old employer.

As these examples make clear, Nevada lawmakers need to implement reforms to more closely police state contracts and to ensure agencies enter deals with additional protections for taxpayers.