EDITORIAL: Theory meets reality at the school district

Behavioral economics strives to understand human behavior and what makes people do the things they do. It’s an academic discipline that somebody in the Clark County School District would do well to study up on.

In recent months, district officials — with all their advanced academic degrees — have expressed surprise and amazement that if you create incentives for students to act in an irresponsible manner, you’ll generate more ill-advised behavior. For many high schoolers, the path of least resistance is irresistible. Every parent of a teenager understands this. So how is this news to those running the nation’s fifth-largest school district?

Last week, the Review-Journal’s Lorraine Longhi reported that, as of March, 39 percent of local public school students were categorized as chronic absentees this academic year, meaning they haven’t shown up to class at least 10 percent of the time. The number should astonish even the district’s most hardened cynics.

District administrators offered a litany of excuses, including the pandemic, the fallout from distance learning and the lack of “culturally responsive pedagogies” to attract minority students. To address the matter, the district is holding student focus groups to investigate what can be done to lure truants back to the classroom. It has also retained “outside partners” — your tax dollars at work — to offer advice and is looking for ways to increase “connectedness,” Ms. Longhi reports.

But instead of groping around like Mr. Magoo, perhaps district officials should take a cue from Occam’s razor, which posits that the simplest explanation tends to be the right one.

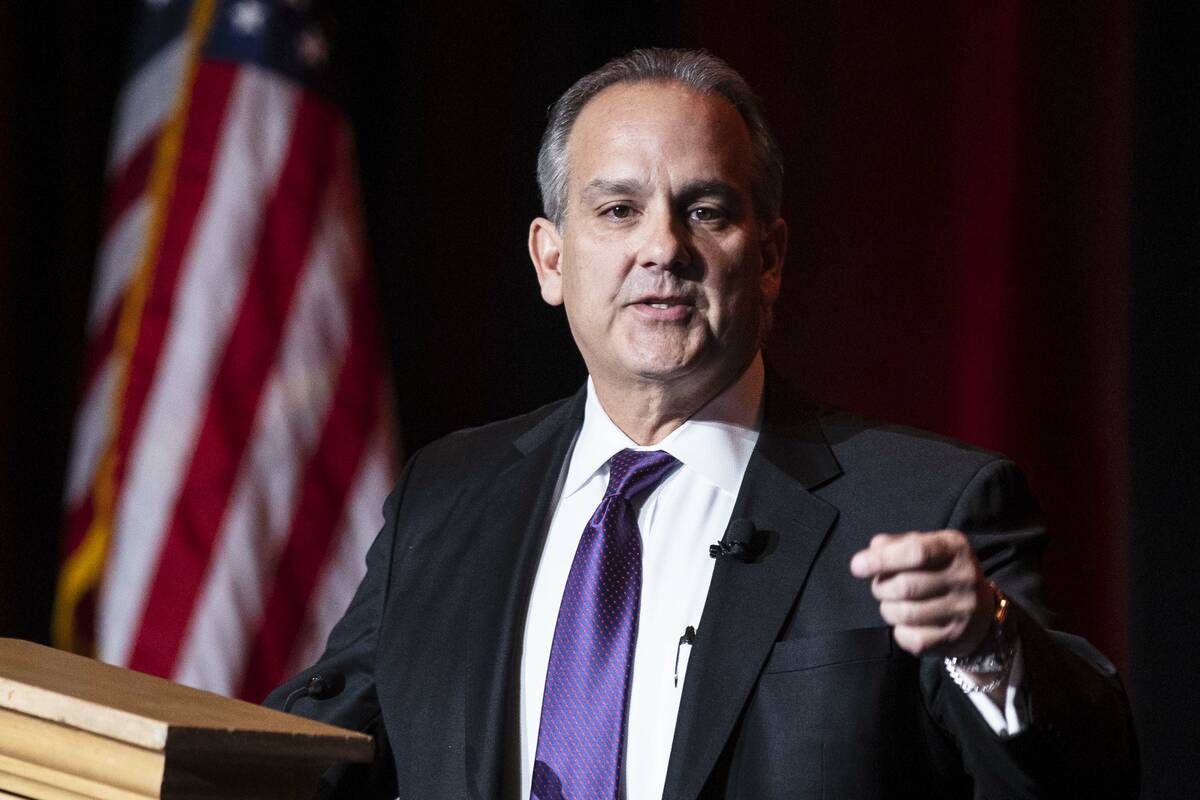

Less than a year ago, Superintendent Jesus Jara pushed through the pliant School Board a radical grading reform that watered down academic standards in a transparent effort to artificially boost graduation rates. Among the changes was an edict that banned behavior, attendance or late assignments from factoring into grades. This means students can no longer be failed for rarely showing up to class.

Lo and behold, district officials are shocked — shocked! — that their experiment has increased chronic absenteeism.

A similar obliviousness has been the hallmark of the district’s reaction to soaring rates of campus violence and the increasing number of students gaming the system to take advantage of relaxed academic demands.

As part of the grading changes, the district set a 50 percent minimum mark, meaning students get half credit even if they do no work. Unlimited test retakes are now the norm. The results have been predictable. Teachers report that the number of kids ignoring homework assignments has increased, and that more middling students don’t bother studying for tests they can take again and again. The result has done little to hurt the most motivated and highly performing kids, but it’s a looming disaster for the rest. “If you think any meaningful learning takes place by completing 20 percent of the work in any subject,” one local educator wrote online, “then keep dreaming!”

All this follows in the arc of the district’s foray into “restorative discipline,” an effort to equalize the number of suspensions and expulsions by race. While imposing harsh disciplinary measures should indeed be a last resort, the practical effect of the policy was to make it more difficult for teachers to rid their classrooms of disruptions, and it sent a clear message to students that there would be minimal consequences for misbehavior. Not surprisingly, incidents of violence on campus — including attacks on teachers — have soared, with more than 3,000 assaults, battery cases and fights since the start of the school year.

In a recent letter to the Review-Journal, one teacher noted that many district students have “somehow internalized the notion that passing a course is some perfunctory exercise, requiring little effort or commitment.” Sad, but entirely foreseeable when district officials abandon attendance requirements, lower academic standards and tolerate errant behavior.

Mr. Jara and his team need to connect the dots and dump the misguided discipline, attendance and academic policies they’ve imposed that have created the pathologies they now decry. “Theories look great on paper,” author Richelle E. Goodrich wrote, “until reality scribbles all over the page.” And right now, the page guiding Mr. Jara is illegible.